Published: August 2015

This patient information provides advice on understanding how your healthcare professionals will discuss risk with you.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

Risk is the chance that any activity or action could happen and harm you. Almost everything we do has an associated risk. Living is a risky business. People will generally take risks if they feel that there is an advantage or benefit. We need to look at risks and benefits together. Normally the benefits of an action should outweigh the risks. There is no such thing as a zero risk. How you view risk depends to a large extent on your own circumstances and ‘comfort zone’.

This information will help you understand how your healthcare professionals will discuss risk with you in relation to your health care and medical treatment.

This information covers:

- why you need to know about risk

- how risk is discussed

- how risk is presented in everyday life

- the best ways for risk to be explained

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms.

Understanding risk

Sometimes research evidence may not be clear about a particular risk or benefit. This is why you may receive different information from different healthcare professionals. It may be because of the situation in which your healthcare professional is working, their own personal experience, your personal situation or because the true risk is not known. Uncertainty exists.

Understanding risk can be difficult but it is helpful when you work in partnership with your healthcare professional.

Reference

Calman KC, Royston G. Personal paper: Risk language and dialects. British Medical Journal 1997;315:939–42.

When you are considering having a procedure, intervention or screening test for yourself or someone else, you need to know about the benefits and risks or any uncertainties to help you to make an informed decision.

How you view a risk depends on one or more of the following:

- the chance of the event occurring (frequency)

- the chance of a condition being detected by a screening test (detection rate)

- the benefits of the treatment or screening

- how much harm may be caused:

- if it is life-threatening

- if it is short-term (temporary) or long-term (permanent)

- how much you feel in control of the decision

- how much you trust the person discussing the risk with you

- whether you feel you understand the situation sufficiently.

Some of these factors will be more important to you than others.

Healthcare professionals use research evidence to describe the chance of an event occurring in the context of an entire population. So your healthcare professional can tell you one woman in nine (1 in 9) will develop breast cancer. What they cannot tell you is whether the ‘one’ woman who develops breast cancer will be you.

If you have a screening test for a particular condition or disease, the results tell you if you are at ‘high risk’ or ‘low risk’ for that condition or disease. For example, if you are pregnant you will be routinely offered a screening test for Down syndrome. The results of this test will show if your unborn baby has a ‘high risk’ or a ‘low risk’ of having Down syndrome. A high-risk result does not mean that your unborn baby definitely has Down syndrome. It means that the risk of Down syndrome is more than 1 in 250 (of 250 pregnant women, more than one woman has an unborn baby with Down syndrome). In this situation, you would be offered a further test to find out if your unborn baby is one of the babies with Down syndrome.

Even if you have a low-risk result, there is a chance that your unborn baby may have Down syndrome but it may be helpful to know that the chance is small.

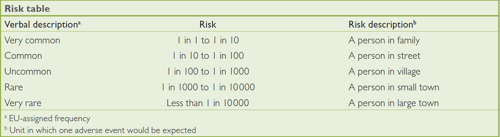

Risk can be given as numbers or words, or both. This table below shows how risk should be described in healthcare:

People’s views of the descriptions of ‘very rare’ or ‘common’ regarding harm or satisfaction vary greatly concerning health care. Your concerns, anxieties and fears about the present and the future are very personal and may affect how you view risk. Some people find it is more useful to discuss risk using numbers or pictures rather than words.

Health risks are talked about every day – sometimes well, sometimes poorly.

Often it can be difficult to sort out the real facts of a matter. Take, for example, the confusion over the 1995 ‘pill scare’. Scientists reported that some oral contraceptives doubled the risk of thromboembolism (a blood clot) compared with other oral contraceptives. To say that something ‘doubles’ sounds a huge amount. What the initial report did not mention, however, was that the risks were only 1 in 6000 to start with – which is ‘rare’. The new risk – 1 in 3000 (or 2 in 6000) – is still rare. In addition, the increased risk of death was only about one person in a million. The risk had not been put into context and a result there was panic in the media and among the public.

Sometimes percentages are used when the overall numbers are very small indeed. It is very important that the facts are explained in a meaningful way.

Good communication between you and your healthcare professional promotes a trusting relationship and brings greater satisfaction to you both. It also helps you to take more responsibility for decisions about your own health care.

When explaining risk healthcare professionals should:

- involve you fully

- give you the opportunity to have someone with you (such as a friend, partner or relative)

- know and understand your circumstances and how this could affect you personally

- describe the risk in different ways; for example, ‘your risk of breast cancer is 1 in 9 or your chance of never getting breast cancer is 8 in 9’

- give you correct and up-to-date information

- give you information that is relevant to you

- be honest, frank and open

- speak clearly

- have empathy

- listen to your concerns

- give you an opportunity to ask questions

- give you time

- provide sources of information such as leaflets or websites

- check that you have fully understood

. . . and on your part, you should:

- say if you don’t understand

- ask if you want information presented in a different way

- say if you need more time.

Your healthcare professional may explain the information in a number of different ways, such as pictures, graphs and other tools to help you make a decision. These help to ensure a better understanding.

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions, if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Clinical Governance Advice No. 7, Presenting Information on Risk (December 2008). The clinical governance advice contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

This leaflet was reviewed before publication by women attending clinics in in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Surrey and by the RCOG Women’s Network.

This patient information leaflet is based on the RCOG’s Clinical Governance Advice Presenting Information on Risk, which contains a full list of the sources of evidence used to produce this guidance.