Published: July 2017

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

This patient information page provides advice if your baby is breech towards the end of pregnancy and the options available to you.

It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who is in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

This information is for you if your baby remains in the breech position after 36 weeks of pregnancy. Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies.

This information includes:

- What breech is and why your baby may be breech

- The different types of breech

- The options if your baby is breech towards the end of your pregnancy

- What turning a breech baby in the uterus involves (external cephalic version or ECV)

- How safe ECV is for you and your baby

- Options for birth if your baby remains breech

- Other information and support available

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms.

Key points

- Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36–37 weeks of pregnancy most babies will turn into the head-first position. If your baby remains breech, it does not usually mean that you or your baby have any problems.

- Turning your baby into the head-first position so that you can have a vaginal delivery is a safe option.

- The alternative to turning your baby into the head-first position is to have a planned caesarean section or a planned vaginal breech birth.

Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies. Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36-37 weeks of pregnancy, most babies turn naturally into the head-first position.

Towards the end of pregnancy, only 3-4 in every 100 (3-4%) babies are in the breech position.

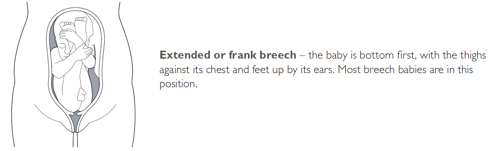

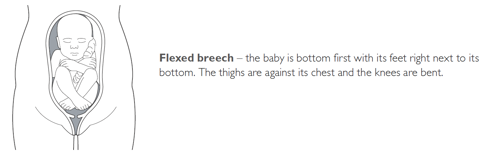

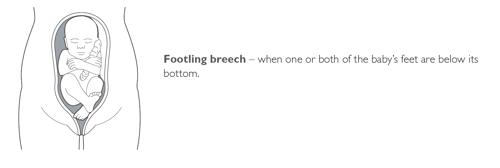

A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions:

It may just be a matter of chance that your baby has not turned into the head-first position. However, there are certain factors that make it more difficult for your baby to turn during pregnancy and therefore more likely to stay in the breech position. These include:

- if this is your first pregnancy

- if your placenta is in a low-lying position (also known as placenta praevia); see the RCOG patient information Placenta praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- if you have too much or too little fluid (amniotic fluid) around your baby

- if you are having more than one baby.

Very rarely, breech may be a sign of a problem with the baby. If this is the case, such problems may be picked up during the scan you are offered at around 20 weeks of pregnancy.

If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy, your healthcare professional will discuss the following options with you:

- trying to turn your baby in the uterus into the head-first position by external cephalic version (ECV)

- planned caesarean section

- planned vaginal breech birth.

What does ECV involve?

ECV involves applying gentle but firm pressure on your abdomen to help your baby turn in the uterus to lie head-first.

Relaxing the muscle of your uterus with medication has been shown to improve the chances of turning your baby. This medication is given by injection before the ECV and is safe for both you and your baby. It may make you feel flushed and you may become aware of your heart beating faster than usual but this will only be for a short time.

Before the ECV you will have an ultrasound scan to confirm your baby is breech, and your pulse and blood pressure will be checked. After the ECV, the ultrasound scan will be repeated to see whether your baby has turned. Your baby’s heart rate will also be monitored before and after the procedure. You will be advised to contact the hospital if you have any bleeding, abdominal pain, contractions or reduced fetal movements after ECV.

ECV is usually performed after 36 or 37 weeks of pregnancy. However, it can be performed right up until the early stages of labour. You do not need to make any preparations for your ECV.

ECV can be uncomfortable and occasionally painful but your healthcare professional will stop if you are experiencing pain and the procedure will only last for a few minutes. If your healthcare professional is unsuccessful at their first attempt in turning your baby then, with your consent, they may try again on another day.

If your blood type is rhesus D negative, you will be advised to have an anti-D injection after the ECV and to have a blood test. See the NICE patient information Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for women who are rhesus D negative, which is available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta156/informationforpublic.

Why turn my baby head-first?

If your ECV is successful and your baby is turned into the head-first position you are more likely to have a vaginal birth. Successful ECV lowers your chances of requiring a caesarean section and its associated risks.

Is ECV safe for me and my baby?

ECV is generally safe with a very low complication rate. Overall, there does not appear to be an increased risk to your baby from having ECV. After ECV has been performed, you will normally be able to go home on the same day.

When you do go into labour, your chances of needing an emergency caesarean section, forceps or vacuum (suction cup) birth is slightly higher than if your baby had always been in a head-down position.

Immediately after ECV, there is a 1 in 200 chance of you needing an emergency caesarean section because of bleeding from the placenta and/or changes in your baby’s heartbeat.

ECV should be carried out by a doctor or a midwife trained in ECV. It should be carried out in a hospital where you can have an emergency caesarean section if needed.

ECV can be carried out on most women, even if they have had one caesarean section before.

ECV should not be carried out if:

- you need a caesarean section for other reasons, such as placenta praevia; see the RCOG patient information Placenta praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- you have had recent vaginal bleeding

- your baby’s heart rate tracing (also known as CTG) is abnormal

- your waters have broken

- you are pregnant with more than one baby; see the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby.

Is ECV always successful?

ECV is successful for about 50% of women. It is more likely to work if you have had a vaginal birth before. Your healthcare team should give you information about the chances of your baby turning based on their assessment of your pregnancy.

If your baby does not turn then your healthcare professional will discuss your options for birth (see below). It is possible to have another attempt at ECV on a different day.

If ECV is successful, there is still a small chance that your baby will turn back to the breech position. However, this happens to less than 5 in 100 (5%) women who have had a successful ECV.

There is no scientific evidence that lying down or sitting in a particular position can help your baby to turn. There is some evidence that the use of moxibustion (burning a Chinese herb called mugwort) at 33–35 weeks of pregnancy may help your baby to turn into the head-first position, possibly by encouraging your baby’s movements. This should be performed under the direction of a registered healthcare practitioner.

Depending on your situation, your choices are:

- planned caesarean section

- planned vaginal breech birth.

There are benefits and risks associated with both caesarean section and vaginal breech birth, and these should be discussed with you so that you can choose what is best for you and your baby.

Caesarean section

If your baby remains breech towards the end of pregnancy, you should be given the option of a caesarean section. Research has shown that planned caesarean section is safer for your baby than a vaginal breech birth. Caesarean section carries slightly more risk for you than a vaginal birth.

Caesarean section can increase your chances of problems in future pregnancies. These may include placental problems, difficulty with repeat caesarean section surgery and a small increase in stillbirth in subsequent pregnancies. See the RCOG patient information Choosing to have a caesarean section.

If you choose to have a caesarean section but then go into labour before your planned operation, your healthcare professional will examine you to assess whether it is safe to go ahead. If the baby is close to being born, it may be safer for you to have a vaginal breech birth.

Vaginal breech birth

After discussion with your healthcare professional about you and your baby’s suitability for a breech delivery, you may choose to have a vaginal breech birth. If you choose this option, you will need to be cared for by a team trained in helping women to have breech babies vaginally. You should plan a hospital birth where you can have an emergency caesarean section if needed, as 4 in 10 (40%) women planning a vaginal breech birth do need a caesarean section. Induction of labour is not usually recommended.

While a successful vaginal birth carries the least risks for you, it carries a small increased risk of your baby dying around the time of delivery. A vaginal breech birth may also cause serious short-term complications for your baby. However, these complications do not seem to have any long-term effects on your baby. Your individual risks should be discussed with you by your healthcare team.

Before choosing a vaginal breech birth, it is advised that you and your baby are assessed by your healthcare professional. They may advise against a vaginal birth if:

- your baby is a footling breech (one or both of the baby’s feet are below its bottom)

- your baby is larger or smaller than average (your healthcare team will discuss this with you)

- your baby is in a certain position, for example, if its neck is very tilted back (hyper extended)

- you have a low-lying placenta (placenta praevia); see the RCOG patient information Placenta Praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- you have pre-eclampsia or any other pregnancy problems; see the RCOG patient information Pre-eclampsia.

With a breech baby you have the same choices for pain relief as with a baby who is in the head-first position. If you choose to have an epidural, there is an increased chance of a caesarean section. However, whatever you choose, a calm atmosphere with continuous support should be provided.

If you have a vaginal breech birth, your baby’s heart rate will usually be monitored continuously as this has been shown to improve your baby’s chance of a good outcome.

In some circumstances, for example, if there are concerns about your baby’s heart rate or if your labour is not progressing, you may need an emergency caesarean section during labour. A paediatrician (a doctor who specialises in the care of babies, children and teenagers) will attend the birth to check your baby is doing well.

If you go into labour before 37 weeks of pregnancy, the balance of the benefits and risks of having a caesarean section or vaginal birth changes and will be discussed with you.

If you are having twins and the first baby is breech, your healthcare professional will usually recommend a planned caesarean section.

If, however, the first baby is head-first, the position of the second baby is less important. This is because, after the birth of the first baby, the second baby has lots more room to move. It may turn naturally into a head-first position or a doctor may be able to help the baby to turn. See the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby.

If you would like further information on breech babies and breech birth, you should speak with your healthcare professional.

Further information

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions, if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Clinical Guidelines No. 20a External Cephalic Version and Reducing Incidence of Term Breech Presentation and No. 20b Management of Breech Presentation. The guidelines contain a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

This information was reviewed before publication by women attending clinics in Nottingham, Essex, Inverness, Manchester, London, Sussex, Bristol, Basildon and Oxford, by the RCOG Women’s Network and by the RCOG Women’s Voices Involvement Panel.