Published: February 2022

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

This information is for you if you want to know about having a cervical stitch, which is also called cervical cerclage.

You may also find it helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who is in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms.

Key points

- You may be offered a cervical stitch if you are at risk of giving birth early.

- A cervical stitch may help to keep your cervix closed and may reduce the risk of you having a late miscarriage or a preterm birth.

- A cervical stitch is usually put in between 12 and 24 weeks of pregnancy and then removed at 36–37 weeks, unless you go into labour before this.

A cervical stitch is an operation where a stitch is placed around your cervix (the neck of your womb) like a purse string, in order to try to keep it closed. It is usually done between 12 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, as a planned procedure, although it may be done at later stages in pregnancy and occasionally before pregnancy

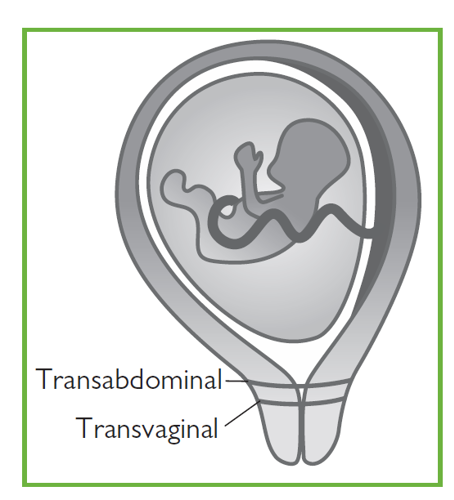

A cervical stitch is more commonly put in vaginally (transvaginal) and less commonly by an abdominal route (transabdominal).

Babies born early (before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy) have

an increased risk of short- and long-term health problems and may

not survive. The chance of health problems is higher the earlier

that the baby is born. Tommy’s (the pregnancy charity) have further

information on premature birth.

There are many reasons why you may give birth early. One

possible cause is because your cervix shortens and opens too

soon. A cervical stitch may help to prevent this by keeping your

cervix closed.

You should be referred to a specialist early in your pregnancy to discuss a plan of care for you if:

- you have had a miscarriage after 16 weeks of pregnancy

- you have had a previous birth before 34 weeks of pregnancy

- your waters broke before 34 weeks in a previous pregnancy, see RCOG information When your waters break prematurely

- you have had certain types of treatment to your cervix (for example, LLETZ or cone biopsy for treatment of an abnormal smear)

- You have scarring to your endometrium (the lining of your

uterus) or your uterus is an unusual shape - You have had a previous caesarean birth when you have

been fully dilated - You have needed a cervical stitch in any of your previous

pregnancies

If you are at increased risk of preterm birth your healthcare team may arrange for you to have transvaginal ultrasound scans to measure your cervix. If it is found to be short (less than 25 mm long), you may be offered:

- a cervical stitch

- a hormonal treatment with progesterone pessaries

- close monitoring by your healthcare team.

Your healthcare professional will discuss the risks and benefits

of these options with you depending on your individual circumstances.

Research is ongoing to understand the best methods to prevent

pre-term birth and you may be invited to take part.

Your healthcare professional should discuss the benefits and risks in your individual situation. Sometimes a cervical stitch is not advised because it may carry risks to you and it would not improve the outcome for your baby. This may be if:

- you have any signs of infection

- you are having vaginal bleeding

- you are having contractions

- your waters have already broken.

If you are pregnant with more than one baby, there is little evidence to show that a cervical stitch will prevent you going into labour early and your care will be individualised depending on your situation. See the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby.

Insertion of a cervical stitch takes place in an operating theatre.

You may have a spinal anaesthetic or a general anaesthetic. If

you have a spinal anaesthetic you will stay awake but will be numb

from the waist down. If you have a general anaesthetic you will be

asleep. Your team will discuss these options with you, to allow you

to choose the best option for you.

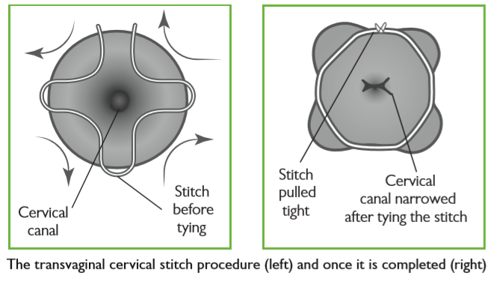

In the operating theatre, your legs will be put in supports and sterile covers will be used to keep the operating area clean. The surgeon will then insert a speculum into your vagina, hold the cervix and put a stitch around it (see the illustration above). The stitch is then tightened and tied, helping to keep the cervix closed. The operation takes less than one hour. You may also have a catheter (tube) inserted into your bladder that will be removed once the anaesthetic has worn off.

You may be offered antibiotics during the operation and you will

be offered medication to ease any discomfort after the surgery.

You are likely to be able to go home the same day although you

may be advised to stay in hospital longer depending on your

circumstances.

This involves an operation to put a stitch around your cervix, through your abdomen, and is also called a ‘transabdominal cerclage’(TAC). It is an uncommon procedure but may be recommended if a vaginal cervical stitch has not worked in the past or if it is not possible to insert a vaginal stitch.

It is done either before you become pregnant or occasionally in early pregnancy.

It may be done through a cut on your abdomen or via keyhole surgery (laparoscopy). This sort of stitch is not removed and your baby would need to be born by caesarean section.

Occasionally, you may be offered a cervical stitch as an emergency procedure after your cervix has already started to open, to help prevent you from having a late miscarriage or early preterm birth. This is called an ‘emergency stitch’ and your healthcare team will discuss the risks and benefits of this with you. This type of stitch has higher risks and is less likely to work than other stitches.

The risks of surgery include:

- bleeding

- injury to your bladder

- injury to your cervix

- your waters breaking early

If your cervix is already too short or too far open it may not be possible to put the stitch in. Even if the stitch is put in successfully it may not always work and you might still experience a late miscarriage or preterm birth.

If you go into labour with the stitch in place, there is a risk of injury to your cervix during labour. A vaginal cervical stitch does not increase your chances of needing induction of labour or a caesarean section.

After the operation, you may have some vaginal bleeding or brownish discharge for a day or two. You should not feel any significant discomfort from the stitch.

Once you recover from the operation, you can carry on as normal for the rest of your pregnancy. The plan of care for you and your baby will be discussed with you. Having a stitch in place will not affect your baby’s growth and development. Resting in bed is not routinely recommended. You can have sex when you feel comfortable to do so although occasionally your partner may be able to feel the stitch during sex.

You should contact your healthcare team if you experience any of the following:

- contractions or cramping abdominal pain

- continued or heavy vaginal bleeding

- your waters breaking

- smelly or green vaginal discharge.

Your stitch will be taken out at the hospital. This will normally happen at around 36–37 weeks of pregnancy, unless you go into labour before then. If you are having a planned caesarean, the stitch can be taken out at the time of the operation.

A speculum is inserted into your vagina and the stitch is cut and removed. You will not normally need anaesthetic for removal of the stitch but occasionally you will be advised by your healthcare professional that this is necessary.

It usually takes just a few minutes and you may experience some discomfort. If you are concerned about pain during removal of the stitch, you can discuss your pain relief options with your healthcare professional.

You may notice some blood staining or vaginal spotting afterwards. This should settle within 24 hours but you may have a brown discharge for longer. If you have any concerns, you should tell your healthcare professional.

Most women do not go into labour immediately after their stitch is removed.

If you go into labour with the cervical stitch still in place, you should contact your maternity unit straight away. It is important to have the stitch removed to prevent damage to your cervix.

If your waters break early but you are not in labour, the stitch will usually be removed because of the increased risk of infection. The timing of this will depend on your indvidual situation.

If you have had a stitch previously, you may be offered a stitch again in a future pregnancy. You should be referred to a specialist clinic early in your next pregnancy to discuss a plan of care for you.

The nature of gynaecological and obstetric care means that intimate examinations are often necessary.

We understand that for some people, particularly those who may have anxiety or who have experienced trauma, physical abuse or sexual abuse, such examinations can be very difficult.

If you feel uncomfortable, anxious or distressed at any time before, during or after an examination, please let your healthcare professional know.

If you find this difficult to talk about, you may communicate your feelings in writing.

Your healthcare professionals are there to help and they can offer alternative options and support for you.

Remember that you can always ask them to stop at any time and that you are entitled to ask for a chaperone to be present. You can also bring a friend or relative if you wish.

Further information

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline 25 Preterm Labour and Birth

A full list of useful organisations (including the above) is available on the RCOG website

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions, if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 75 Cervial Cerclage published February 2022 and on NICE guideline 25 on Preterm Labour and Birth, published in November 2015. The guideline contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.